We are excited to feature a guest post from actual doctors on the nitty-gritty of school reopening. This post is taken from Emily Oster’s newsletter (found here). Westyn Branch-Elliman (MD, MMSc) and Elissa Perkins, (MD, MPH) weigh in below about the logistics of schools reopening. They offer a smart perspective on why we should be willing to put a lot of resources into this endeavor and also exactly what resources we might put in. Enjoy!

COVID-19 is out of control in this country. Why are we even talking about opening schools? Shouldn’t we just wait it out until we have a vaccine?

The often-voiced idea of keeping students and staff home, and utilizing virtual learning “until it is completely safe” is predicated on the notion that a safe and effective vaccine is on the horizon — maybe even this fall or early winter. Delaying openings until January suggests that things will be different in January. But the reality is that development of vaccines can take years, and once a candidate vaccine is developed, it needs to be tested for both safety and for efficacy — and that process takes time too. If an effective vaccine is identified, then distribution takes time, and a large portion of the population will need to be vaccinated in order for the virus to cease to have a major impact on our daily lives. Thus, we need to think about how we are going to manage this pandemic over years, two to three at the minimum, not months. Unfortunately, we also have to consider the possibility that a safe and effective vaccine may never be developed.

Given the uncertainty, reliance on an effective vaccine to solve the return-to-school problem is unrealistic, and other strategies that may at first glance seem too difficult or too expensive must be developed and implemented. If the position adopted by society is: “not until it is completely safe,” then we have to recognize that the kindergarteners who left their elementary schools in March of 2020 may never see the inside of those buildings again. This is not feasible. Thus, we really need to shift the conversation from “perfectly safe” and “only if there is vaccine” to “how can we do this as safely as possible?” and “what resources do we need in order to achieve this common goal?”

Adding this perspective to the debate over school reopening shifts the entire framework of the discussion. First, it points toward a need to “go long” and think big — bigger than the fall, bigger even than the current academic year. We must think about school plans over a three-year horizon, which may mean capital investments that may seem excessively costly upfront, but over time will be worthwhile, particularly if we consider that these investments will keep children and teachers safe. Second, shifting from a short-term to a long-term view of the pandemic points us to focus on risk mitigation, rather than risk elimination. To optimize safety, we need to develop and implement policies and processes that do not put in-person learning on hold until the pandemic is over, but rather adopt and adapt infection control strategies that have been clearly demonstrated to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Achieving these infrastructure changes will require major investments, both in terms of cost and labor — but these investments are worth it when we consider that this pandemic may be something we just have to learn to live with. Already during this pandemic, the Army Corps of Engineers has been called up to build COVID-19 hospitals. Could they be called to build tents for schools, or other temporary structures to facilitate a full return of students to “classrooms?” Would volunteers in the community be willing to pitch in? Could Habitat for Humanity or other charitable organizations leverage its workforce and network to build new schools? Could we repurpose empty office spaces as school classrooms? Reopening schools will require investment from parents, the community, state and local governments, and the federal government. Given the already late date, we need to take action now.

A question I’m guessing we are all getting recently… You heard about the cluster of cases at the Georgia camp? Given what happened there, how could you possibly think about reopening schools?

The large cluster at the Georgia camp, coupled with the recent article in JAMA Pediatrics demonstrates two important points: First, kids can become infected, and second, they can spread the virus. We still do not fully understand the role of young children and teenagers in this pandemic, since schools largely closed when it began. However, one of the most important concepts in infection prevention is the idea of universal precautions. When we draw blood, we always assume that anyone can have an infection, and we behave accordingly. We need to think the same way when it comes to children and COVID.

The camp cluster does highlight several important concepts as we think through these questions. We have many tools in our prevention arsenal, but none is foolproof. We must use science and the best available evidence to inform our infection control plans. This will optimize safety and limit spread.

The Georgia camp with the large outbreak had a lot of COVID in the community when the camp opened, and they did not leverage all of the infection control tools in our toolbox. The camp primarily relied on a few strategies (mostly outdoor settings, where natural airflow provides protection, and to some extent distancing), but only intermittently, and they overlooked major cornerstones of infection control. A truly multi-faceted plan would have included personal protective equipment strategies, such as mandated masks and/or face shields for campers in addition to staff (especially indoors), daily symptom screens, and avoidance of high-risk activities, like indoor singing and cheering.

There is a lot of talk about the relationship between reopening and community rates. Do you have a cutoff for how low the virus needs to be in the community to open schools?

Just as we cannot resume high risk indoor activities, we cannot re-open schools safely in communities with uncontrolled spread. We need more research to determine exactly what “high rates of community spread” means, but we think less than 5% test positivity, and probably closer to 3%. (Of note for the last question: The test positivity rate in Georgia is closer to 16%.)

What kind of strategies?

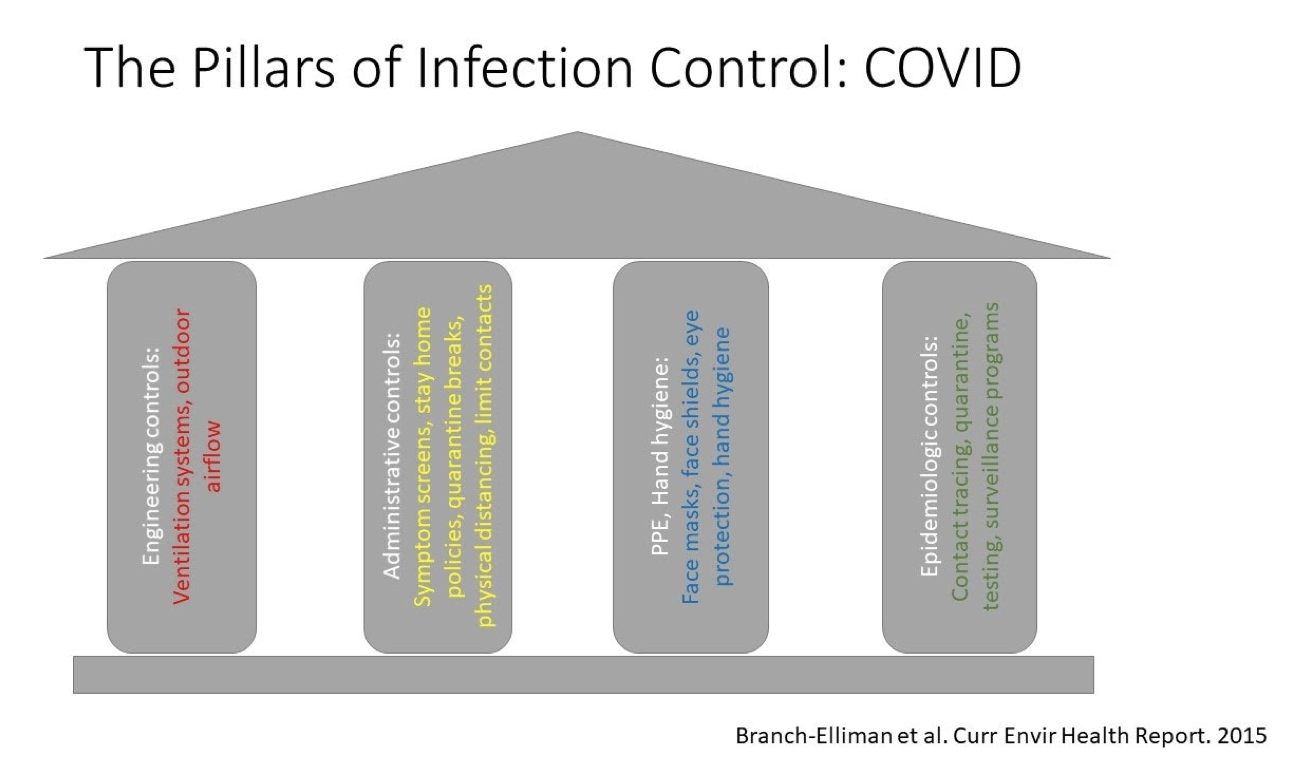

Within infection control, there are several “buckets” of prevention strategies. When we think about building a program, we want to pick multiple strategies from multiple categories in order to make sure we maintain safety if one of them fails. We learn in geometry that three points determine a plane. So why do most chairs have four legs? Partially, it is to ensure we have a back up if one of them fails. Same concept applies in infection control.

Broadly speaking, for COVID prevention, we have options listed below.

Engineering/environmental controls: These are interventions “built in” to the physical plant. Some examples include ventilation systems and using outdoor spaces (which has a long history in infection control).

Administrative controls: These are policies that are designed to limit the spread of infection. Some examples include rules about class sizes/number of interactions, physical distancing, changing the school calendar, pre-screening tools, and cancelling high-risk activities, such as singing.

Epidemiologic controls: These are strategies that are focused on cluster identification and tracing. Examples include periodic surveillance testing, quarantining when sick, and mandatory vaccination programs.

Personal protective equipment and hand hygiene: This category includes things that everyone can do to limit the spread of the disease, and includes wearing a face mask and/or a face shield, and wearing eye protection. Hand hygiene, with either soap and water or sanitizer, reduces the chances of self-inoculation and the spread of COVID and other infections. In some cases, one type of intervention (e.g. utilizing outdoor spaces) may fall into more than one category, for example by improving ventilation (an engineering/environmental control) and also by allowing children and teachers to spread out (an administrative control).

Various strategies that could be used to support safe reopening are discussed in more detail below, and here. Ideally, many of these strategies would be used in combination, rather than isolation, in order to facilitate the safest possible re-opening strategy. As we mentioned above, we want to make sure that there is always a “back-up” strategy in case one of the infection control tools fails.

Testing and contact tracing

Finding cases and implementing isolation before they become clusters is a critical aspect of pandemic control. This means we need to find ways to make testing widely and rapidly available, with rapid turnaround time so results are quickly obtained, before spread spirals out of control. We also think it is important that we find effective ways to track results of surveillance testing, so that results do not fall through the cracks.

Engineering controls and infrastructure adaptations

Given that droplet-based transmission is the predominant mode of spread, the ability to maintain physical distance is an important infection control measure. Evidence is mounting that cases peaked in places with high rates of indoor interactions — the Northeast in late winter and spring, and the South in the summer. Air conditioning and heating use are among the strongest predictors of high levels of spread, and a study of 318 outbreaks involving 1245 cases found that only one outbreak involving two cases occurred in an outdoor setting. This underscores the critical importance of good engineering controls and use of outdoor spaces when possible. A critical aspect of preventing transmission is good ventilation, which can be achieved through retrofitting school buildings, which may be challenging and cost-prohibitive, or by leveraging natural airflow.

Given the value of natural outdoor airflow for limiting transmission, could we move some or all instruction outside? This would likely require major challenges to the school calendar and also major investments in infrastructure (i.e. outdoor tents?). But if we could achieve it, it could improve safety by improving air flow and allowing more physical distancing.

If a school’s footprint is too small to support additional outdoor infrastructure, another consideration is creative thinking to expand the amount of physical space available. This could include “in-kind” donations from local residents in the form of land or building use. Other town infrastructure, such as library buildings, parking lots, and parks, should also be considered as possible swing spaces for outdoor classrooms and temporary structures to maximize the potential for a full and safe reopening.

Are there other administrative controls we could consider?

While it might be difficult to implement, we could think about changing the school calendar, for example by substituting “summer break” for “winter break” in the colder areas of the country. This might make it easier to hold classes outside, to give kids mask breaks, and to let them spread out, but would be a major change from how we traditionally think about the school year.

We could also think about pooling all of the single days off (e.g. three-day weekend, teacher training, etc.) and scheduling them all to occur at the same time, rather than one at a time mixed-in throughout the school calendar. By scheduling all of these days off together, we could build mandatory “quarantine breaks” into the schedule, which is another creative way to combat spread.

Pre-screening questionnaires to limit exposures

Control of spread in healthcare settings included multiple interventions, including daily “symptom screens” prior to presentation to work, often online or automated through an app-based system. These questionnaires asked about fevers, cough, and other relevant COVID-19 symptoms, and also asked about travel. These screening tools were not designed to be perfectly predictive of COVID-19, but prevented providers with symptoms and or travel to high prevalence areas from coming to work, potentially spreading other infections, and preventing transmission of other respiratory viral infections to their co-workers that necessitated additional testing and contact tracing. A similar system could easily be adapted for students and parents to complete on a daily basis to reduce the chances that a child will become sick while at school, triggering a full-class quarantine and screening.

You talked a lot about what can be done on a facility and policy level to prevent spread. Are there things parents can do personally?

Face coverings are an important aspect of pandemic control. This includes masks, of course, but also shields and barriers. We must recognize that full-day compliance is hard, and develop plans that are safe, practical, and feasible for implementation in a classroom setting.

Face masks are more difficult to use for many hours at a time, often quickly get soiled, and encourage fidgeting and the child touching their face, none of which promote good infection control practices. We are still waiting for more data about face shields, however, they are particularly attractive for implementation in elementary room settings because they are comfortable, reusable, easy-to-clean, and allow for students and teachers to see each other. A recently released pre-print, while not peer reviewed, is very encouraging that face shields may provide at least as much protection, if not more, than face masks. If data continues to emerge about the safety of face shields for community use, we need to be willing to adapt plans (e.g. by allowing a transition to face shields if they are found to be more effective in real-world settings) and recognize that any plan that we develop now may need to be updated, or fully changed, in the future. All PPE, in addition to providing protection, also provides a physical barrier that minimizes face touching and eye rubbing.

As someone who has to wear a mask all day, I also recommend these headbands—they take a lot of the pressure off of your ears, and they can help keep the mask in place when the bands start to stretch out. In addition, I find that they keep the mask in place when I am talking, which is another big plus. Personally, I prefer the ones with two buttons, but there are different versions, and people should plan to try out their PPE before it needs to be used all day, to ensure they can find something comfortable for them.

What about hand washing?

Hand hygiene programs have been clearly demonstrated to reduce the spread of infections within schools, and also to reduce absenteeism, but, again practicality and feasibility are major concerns. Although current CDC guidelines suggest that soap and water is superior to hand sanitizer, this finding has not been demonstrated in real-world settings, as compliance with proper soap and water technique is challenging. Thus, we encourage an approach in which all students have ready access to hand sanitizer, with soap and water strategies saved for when you get really messy, or after the bathroom.

What about ventilation systems?

Ventilation systems are clearly an important consideration in any infection control plan. As discussed in more detail above, improving ventilation is an engineering control that we can use to prevent the spread of infection in various ways, including through filtration of small particles. Engineering controls are attractive because, unlike, other strategies, they do not rely on day to day compliance with personal protective equipment. Unfortunately, some engineering controls can also be difficult to implement, as many older air systems cannot support small filters safely, upgrading systems can take a long time, and the cost of retrofitting can be prohibitive for school budgets. Due to cost and feasibility, other strategies, such as opening windows to improve airflow, and HEPA filters in classrooms, are easier and potentially more attractive ways to address this issue on a large scale.

These are some really interesting ideas. How can we make them work in the “real world?”

Thinking about implementation is important, and one of us (Westyn) is trained in this field. Critical to the success of any infection control program are feasibility, acceptability, and practicality. Recognizing the importance of these implementation outcomes, we have to recognize real-world challenges and develop strategies that children can adhere to. Engineering controls are attractive partially because they do not require daily sustainment, and experiences from re-openings in Israel suggests that lack of adherence and unworkable plans contributed to their school-based clusters.

We also need to think about building protections into any program, so that we do not rely on any one strategy at a time. For example, when children are eating, wearing a mask is not possible, which means we need to employ different prevention strategies during mealtimes. Preliminary data from a hospital cluster suggests that shared eating spaces can lead to super-spreading events. We know that, due to natural ventilation, outdoor spaces are the safest. Thus, can we substitute outdoor cafeterias for masks at mealtimes, swapping one strategy for another? If that cannot be accomplished, then we need to think about other types of infection control strategies, such as administrative controls. This might mean that children do not go to school for the full day, so that students and staff can eat at home, rather than at school.